2022.10.21

Seunghee You

Seunghee You

“To show human beings as excessively beastlike without revealing their greatness is dangerous.

Likewise, to emphasize their greatness without acknowledging their baseness is equally dangerous.

To leave people unaware of both aspects is even more perilous.

Yet to reveal these two sides together is profoundly beneficial.” ¹

Likewise, to emphasize their greatness without acknowledging their baseness is equally dangerous.

To leave people unaware of both aspects is even more perilous.

Yet to reveal these two sides together is profoundly beneficial.” ¹

Recently, Elon Musk (1971–) unveiled the humanoid robot Optimus.

At the event, he stated that his goal was to develop Optimus with high performance and to popularize it by making it affordable to the public. Today, humanoid robots are no longer merely machines that resemble humans; they are moving toward becoming “second humans” that coexist with and participate in everyday human life.

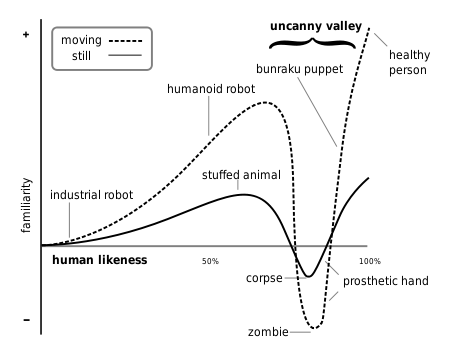

In contrast to this contemporary trajectory, Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori (森政弘, 1927–) proposed a critical distance between humans and machines through his hypothesis of the Uncanny Valley (Bukimi no Tani; 不気味の谷). According to this theory, as robots become more human-like, people’s sense of affinity toward them increases. However, when a robot becomes too similar to a human, this affinity suddenly turns into a sense of eeriness—comparable to the unsettling feeling evoked by corpses or zombies. This phenomenon appears as a “valley” in the graph, where the curve drops sharply after reaching its first peak.

출처: wikipedia

Accordingly, Mori argued that in order to avoid falling into the uncanny valley, an appropriate distance between humans and machines should be maintained, and he proposed non-human design as one possible solution. However, as exemplified by Optimus mentioned earlier, the present situation differs significantly from that of the 1970s, when Mori first formulated the uncanny valley hypothesis. In the twentieth century, not only roboticists but most people shared the belief that machines could never become human. By contrast, twenty-first-century humanoid robots have reached a level at which they resemble humans not only in appearance but also in behavior and modes of thinking. Public responses to this resemblance have likewise become largely positive.

Many humanoid robots are modeled after white celebrities such as Scarlett Johansson, and even Korean virtual models like Rozy possess appearances designed to appeal broadly to the public. In this contemporary context, the question of whether an entity is human or robot has become less significant than the degree of likability embedded in its appearance. At a time when technology has become inseparable from human life, robots have come to occupy a position as one of the entities that constitute the world. For this reason, Mori’s uncanny valley hypothesis reveals certain limitations when applied to the present moment, given the historical shift from a period in which robots were unfamiliar and perceived as unsettling, to one in which they have become familiar and are regarded as homogeneous beings.

Nevertheless, the concept of the uncanny valley remains highly suggestive when considering the fact that technology now occupies a position of superiority over humans. Through the uncanny valley, it becomes apparent that the discomfort humans once felt toward robots is no longer fully operative today. This shift indicates that the relationship between humans and technology has departed from its traditional form and has, in fact, been inverted. At the same time, although the eerie feeling once triggered by robots that closely resemble human form has largely disappeared through familiarity, fear, rejection, and discomfort persist at points where technology is perceived to encroach upon the human domain. In this sense, Mori’s uncanny valley retains its relevance in contemporary discourse.

Furthermore, the inversion of the relationship between humans and technology reveals a reality in which technology cannot be refused, and in which its acceptance is accompanied by a certain degree of coercion. The forced acceptance of technology inevitably produces forms of alienation, as individuals are compelled to adapt to technological systems. One such form of alienation can be observed in media environments that rely on virtual images for communication, where extreme uniformity emerges through a bias toward idealized forms that attract the most attention—those that receive the most “likes.” Robot expert Christoph Bartneck has pointed out that “robot designers may come from all over the world, but they still idealize white robots.” Although technological development has ostensibly introduced immense diversity, Bartneck’s observation raises doubts as to whether this diversity is truly diverse.

Encountering contemporary science and technology, I find myself simultaneously recognizing human greatness and discovering human baseness. Through baseness, I come to perceive the ignorance and powerlessness that are concealed behind notions of human greatness. Blaise Pascal explains how the contradictory nature of human life—defined by the opposition between greatness and baseness—can ultimately be beneficial to humanity. To understand what it means to be human, one must examine the contradictions that extend toward both extremes, for it is between these poles that human dignity can be found. When dangerous conditions persist, it becomes necessary to examine whether one has leaned excessively toward either side.

What, then, does it mean to be human in the present age? Today, humans enjoy extreme convenience through technological advancements such as autonomous driving, delivery applications, and ride-hailing services like Kakao Taxi. At the same time, there are those who use their own bodies as tools for drug trafficking. So-called “body packers,” who transport drugs by filling their stomachs with narcotics, risk death should even the slightest rupture occur. What meaning does the body hold for them, and what kind of being is the human, such that one can treat oneself as if one were a game character who can simply be revived after death? Is the human body merely a mass occupying space?

Materialism and materialist modes of thought derived from scientific and technological development reduce human meaning to that of matter, scarcely distinguishable from objects. This materialism is further intensified in the virtual worlds of media, where existence becomes increasingly confined to the visual.

¹ Blaise Pascal, Pensées, trans. Hyun Mi-ae (Seoul: Eulyoo Publishing, 2013), 59.